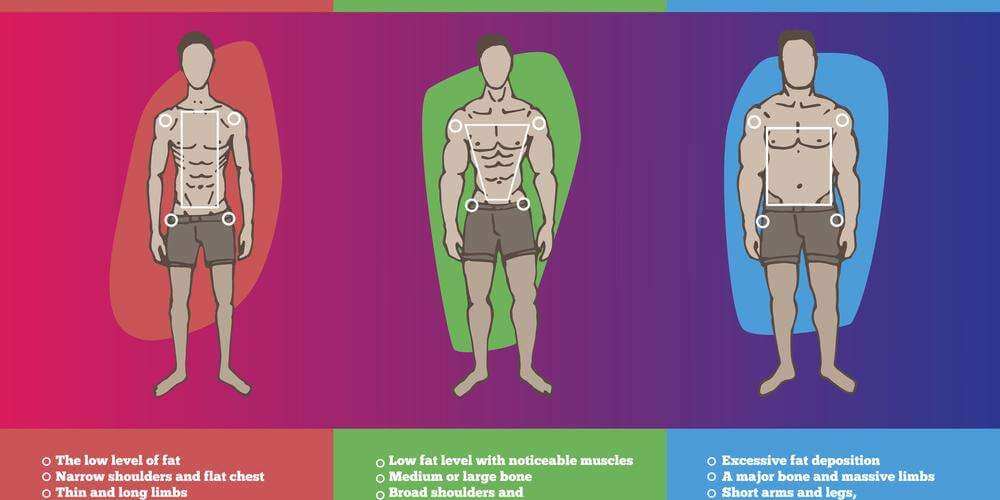

In the 1940s, psychologist William Herbert Sheldon used thousands of photos of naked Ivy League students without their consent to create a classification of the human body shape. He found that our structure can be summarized on 3 dimensions: endomorphy, ectomorphy and mesomorphy. Sheldon’s original works tried to connect our somatotype to our personality and some Nazi-like ideas of human worth. Other scientists of course quickly discredited these ideas, but exercise scientists picked up on the classification. Popular fitness wisdom holds that your primary body type dictates what you’re gifted at and possibly also how you should work out and diet. The theory briefly goes as follows.

- Endomorphs are bulky: they have an easy time gaining muscle and strength but a hard time losing fat. Destined for powerlifting.

- Ectomorphs are tall and skinny hardgainers that effortlessly get ripped but have a hard time putting on muscle. Destined for… the catwalk?

- Mesomorphs have the best of both worlds. Humans supreme destined for the Mr. Olympia.

The 3 body type dimensions are named after the 3 layers of germ during our embryonic development: the inner endoderm develops primarily into our gut; the middle mesoderm develops primarily into our muscles, and the outer ectoderm develops into other things like our skin and hair.

Let’s look at the science of somatotyping. What does your somatotype tell you about how you should work out and diet?

What’s your somatotype: endomorph, ectomorph or mesomorph?

The most established somatotyping method is the Heath-Carter method. This requires measuring various body dimensions with a measurement tape and mathematical formulas to compute the 3 dimensions. Unless you’re an exercise scientist, there’s no need for this level of detail. You can get a good idea of your primary body type simply by looking in the mirror: is your body shape tall and slender (ecto), round and thick (endo) or aesthetic and athletic (meso)? Many studies even go by photos rather than physical measurements in person. Many people fall somewhere in the middle, but you probably have a good idea of your primary type.

What does your body type tell you about how to work out?

In some fitness communities, the idea that your body structure says anything about the physiology of your muscles or body in general is regarded as utter pseudoscience. However, all the way back in 1994, Van Etten et al. already provided hard data that individuals with a solid body build gain more muscle during strength training than individuals with a slender body build.

In some cases, science is stranger than fiction: a ton of research shows the ratio of the length of our index-to-ring finger (2D:4D ratio) is associated with our athletic success. For example, the 2D:4D ratio predicts sumo wrestlers’ rank and can discriminate between recreational and world-class wrestlers. Our 2D:4D ratio correlates with how much testosterone we were exposed to in the womb, which influences many things. The ratio of our finger lengths can even predict to some degree our sexual preferences, how likely it is that someone’s homosexual (intermediate ratio to men and women), and how likely a lesbian is to be ‘butch’ or ‘femme’ [1, 2, 3, 4]. Generally speaking, the longer your ring finger and the shorter your index finger, the more masculine and athletic you’re likely to be.

We also have a study where children were divided into 3 groups: strength training, endurance training or no training. Somatotype significantly influenced the gains in performance measures. For example, mesomorphy was associated with the greatest improvements in sprinting speed, whereas ectomorphy was associated with the greatest improvements in aerobic fitness (‘endurance’). The same performance measures that are positively influenced by our somatotype also seem to result in increased trainability. This is probably in part motivational: we like things we are good at more and therefore put more effort into them. If you’re terrible at running marathons yet excel at sprinting, you probably prefer sprinting. However, there’s probably also a genetic component, as other research finds we make better gains when strength training with a volume and intensity that suits our genotype.

If we make the best gains in fitness on the type of training we’re most gifted for, and our somatotype influences what we’re good at, we should find out which type of exercise our somatotype is best for. There’s a lot of research on this and it’s very conflicted.

- Research on Judokas and recreational trainees finds mesomorphy correlates positively with strength and power and ectomorphy correlates negatively, as you’d expect based on somatotyping theory, but ectomorphy seems to define elite Taekwondo skill rather than mesomorphy.

- In recent research on recreational trainees, mesomorphy positively predicted squat and bench press strength and ectomorphy was detrimental, but endomorphy did not predict strength, and ectomorphy became positively correlated with strength when combined with mesomorphy. Other research [2, 3] confirms mesomorphy positively correlates with strength/power; however, so did ectomorphy, and endomorphy negatively correlated with strength instead of positively in one study.

- The performance measure influences the relations with somatotype. It seems endomorphy is positively related to absolute strength measures but negatively to relative strength, such as bodyweight exercises, for which ectomorphy becomes a positive performance predictor [2].

While somatotype dimensions do a poor job of explaining physical performance, all the above findings make perfect sense for the body composition measures that determine our somatotype. Several studies also measured body fat percentage and lean body mass. When you incorporate these correlations, it’s clear that body composition and not somatotype matters.

- Mesomorphy basically serves as a diluted measure of muscle mass, which is correlated with absolute strength.

- Endomorphy serves as a diluted measure of body fat percentage, which determines strength relative to bodyweight.

- Ectomorphy is basically the opposite of endomorphy relative to height.

So our somatotype tells us nothing about what type of exercise we’re best at that we can’t predict much better based on how much muscle and fat we have and how tall we are. Somatotyping just takes these 3 variables that actually matter and rearranges them into different dimensions, weakening the correlations in the process. To illustrate the meaninglessness of our somatotype, somatotype isn’t that strongly related to grip strength and instead strength is mostly just a function of height.

You may intuitively think other bodily dimensions, such as the length of our femurs, also influences performance. Some people may have a structure that’s better suited for squatting, whereas other people have a structure that’s better suited for deadlifting. Plausible as it sounds, several studies quite consistently show that our anthropometry has little to no effect on powerlifting performance: strength is primarily correlated simply with how much muscle we have, both on the limb-specific and whole-body level [2, 3].

The primary difference between low-level and elite athletes of various sports is also that the elite athletes are more mesomorphic. For almost every sport where strength matters, performance correlates positively with muscularity; and for almost every sport where relative strength matters, performance negatively correlates with body fat percentage. The primary distinction between lower- and higher-level athletes of strength sports is thus not that some people got luckier with their body structure but that the higher-level athletes are just leaner and more muscular. So stop complaining about how long your femurs are and go put some more muscle on them.

In conclusion, your somatotype only matters for your training insofar as it gives a rough indication of your muscle mass and body fat percentage. Your somatotype per se doesn’t change how you should build muscle and strength.

What does your body type tell you about how to diet?

You may expect endomorphs have a slower metabolism, which is why they’re fatter, and ectomorphs have a faster metabolism, which is why they’re leaner. However, somatotype does not appear to correlate with basal metabolic rate (BMR). In a study on Korean football players, goalkeepers had a significantly faster metabolism than the other player positions, yet they had the same somatotype. Their higher BMR was the result of more fat-free mass. Since they were also taller, this did not change their somatotype. This study illustrates again you should think in terms of body composition and height rather than somatotypes.

In fact, any relation between somatotype and diet is likely the other way around. Whether you’re an endomoph is mostly determined by environmental factors (read: your diet), not your genetics, as it’s mostly a function of your body fat percentage, which is in principle entirely under your own control. By losing fat, you can go from endomorph to mesomorph (or ectomorph).

I was probably an endomorph before I started lifting. Certainly not obese but ‘well fed’. After months of training (left photo below), I evolved to an ectomorph. Now I’m a mesomorph.

After months of training on the left, I was still an ectomorph. Years later on the right, I’m ‘suddenly’ a mesomorph.

The only way your body structure influences how you should diet differently than others is in the form of your ideal energy surplus when bulking. Since solidly-built individuals can gain muscle faster than slimly-built individuals, they can benefit from a higher energy surplus. Other than that, all your body type tells you is whether you should focus on cutting (losing fat) or bulking (building muscle), not how to do it.

Conclusion

Your somatotype is just a classification of your current body shape. The diet and workouts you need to change your body shape follow the same principles as for anyone else. We all have a different body structure and some structures may lend themselves better to certain types of exercise than others, but physical performance is mostly determined by your training and body composition, not your somatotype. Your somatotype is also strongly influenced by your height, lean body mass and fat mass. Your body composition in turn is largely determined by your training and diet, not your genetics. You can significantly change your somatotype by getting leaner and more muscular. So there is no such thing as a doomed endomorph. Everyone can get lean. And while some people have to work harder than others to build muscle, virtually everyone can become more mesomorphic.

Your body shape does not define you. You define your body shape.